Modern clinical practice increasingly requires physicians to understand more than laboratory values and imaging results. Patients arrive shaped by the environments in which they live, work, and age. Yet most clinicians have limited access to structured, reliable information about those environments. The December 2025 update to CDC PLACES, released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, offers a practical way to close that gap.

PLACES provides model-based estimates for forty health measures across every U.S. county, city, census tract, and ZIP Code Tabulation Area. These measures include chronic disease prevalence, risk behaviors, disability, preventive care indicators, and selected social needs. For clinicians, the significance lies not in replacing individual assessment, but in adding population context to everyday decision-making.

“Clinical encounters do not occur in isolation. They reflect the communities patients return to after they leave the exam room.”

PLACES is especially useful for clinicians because it offers community-level context without relying on protected health information. The estimates are generated using a small-area estimation approach known as multilevel regression and poststratification. CDC describes PLACES as using this MRP framework to produce estimates for adults aged 18 years and older.

────────────────────────────────────────

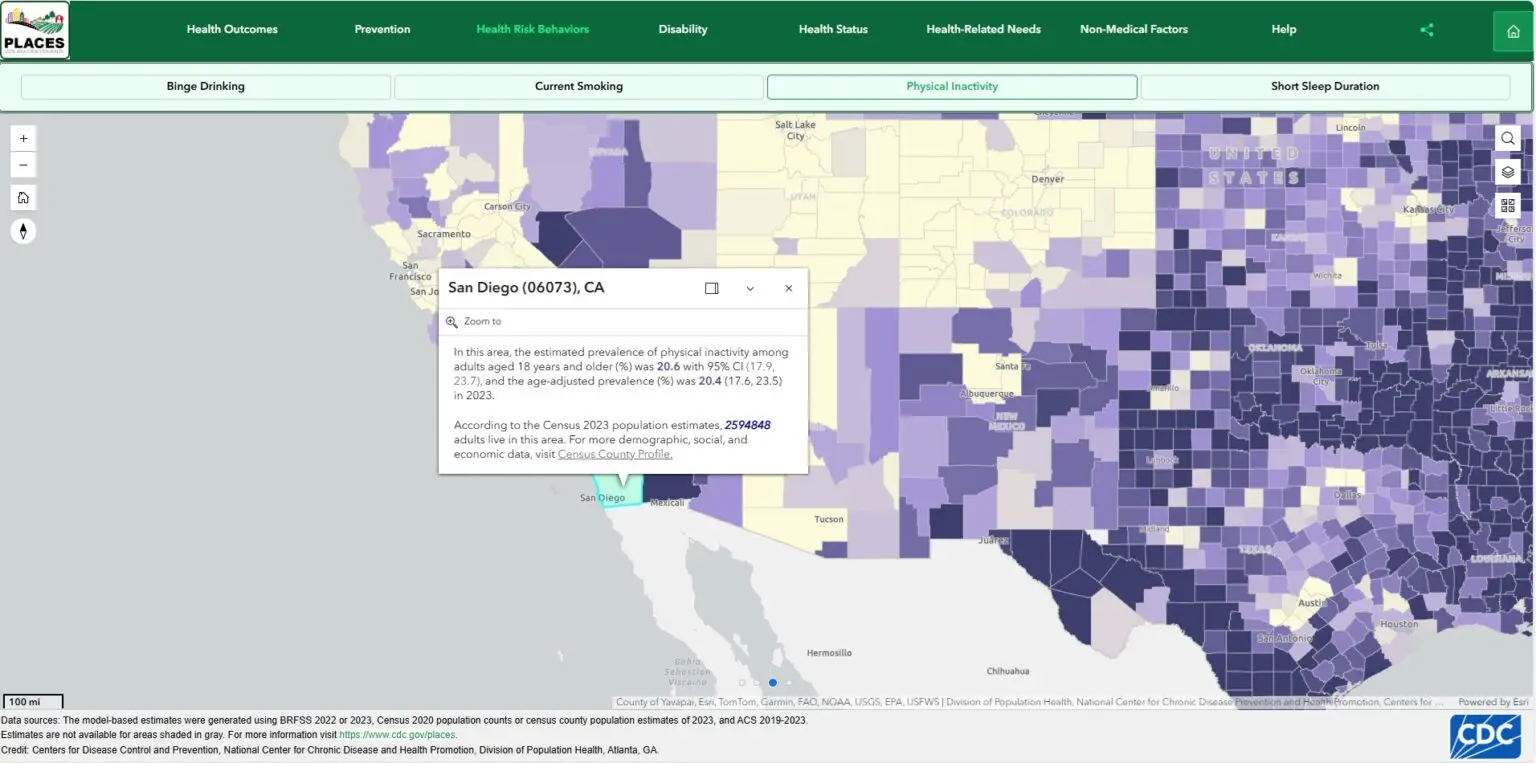

Clinical vignette 1: San Diego County, California

A patient with type 2 diabetes and hypertension keeps missing lifestyle targets. The clinical conversation often stalls at diet and activity recommendations that feel generic and, to the patient, unrealistic. Before the next visit, you open PLACES and review county-level context for San Diego County, focusing on a small set of relevant measures such as diabetes prevalence, obesity, and physical inactivity. You are not using PLACES to make assumptions about this individual patient. You are using it to sharpen your questions and to frame counseling around barriers that are commonly present in the community.

In practice, this shifts the visit from repetition to problem-solving. Instead of “exercise more,” you can ask, “What options do you have for safe activity where you live?” Instead of “eat healthier,” you can ask, “Where do you usually buy groceries, and what feels feasible this week?” PLACES does not replace bedside assessment, but it helps you reach the right questions sooner.

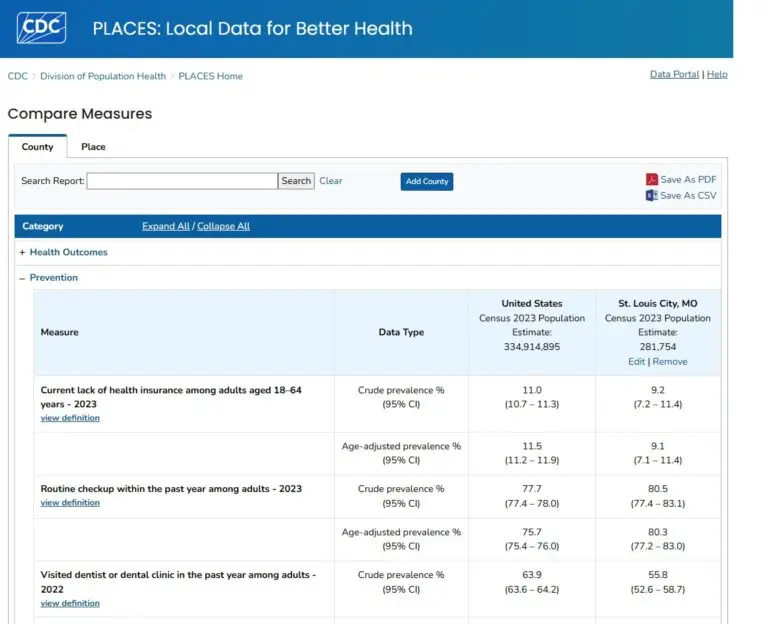

Clinical vignette 2: St. Louis City, Missouri

A resident is preparing a clinic teaching conference on prevention and notices that risk patterns and preventive care gaps vary dramatically across the region. You pull PLACES estimates for St. Louis County and choose a prevention-relevant measure such as smoking, plus one chronic disease measure aligned with your clinic priorities. You turn this into an explicit teaching point: community data can guide outreach and counseling themes, but it must not slide into stereotyping. The purpose is to inform clinical strategy and to promote respectful, individualized care.

This also creates a practical bridge to AI literacy. Because PLACES is public and aggregate, trainees can use it as a safe input for structured summarization exercises, then critique the output for overgeneralization and missing uncertainty.

PLACES does not dictate care. It contextualizes it. For physicians seeking to practice medicine that is both evidence-based and socially aware, this dataset offers a valuable and accessible resource.

Links

https://www.cdc.gov/places/about/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/places/methodology/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/places/tools/data-portal.html